By Michael Barry

In Ghent, Belgium, the low thunder of the cyclists racing into the wooden banking of the velodrome is unheard over the festivities in the track center. A band belts out music as the spectators, dressed in their best clothes, eat, dance and mingle. Few of the spectators hear the yells of the riders as they bump elbows to maneuver for position before the final sprint to the line. These events, the six-day track races, are orchestrated spectacles.

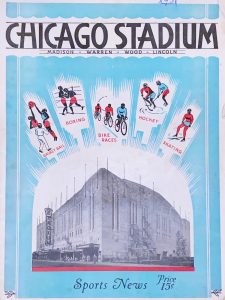

At the turn of the century, cycling was America’s sport. The country’s sporting icons were track cyclists and the arenas now known for their residing hockey and basketball teams were packed with cycling fans cheering for their heroes as they raced around the steeply banked wooden tracks.

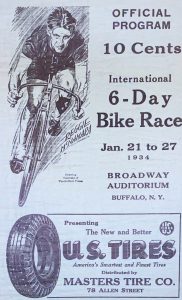

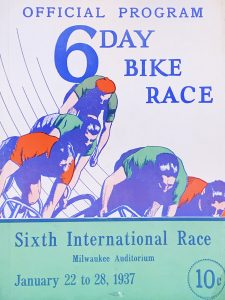

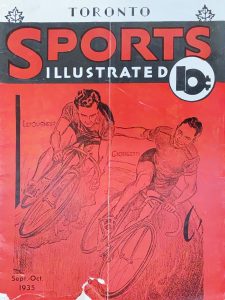

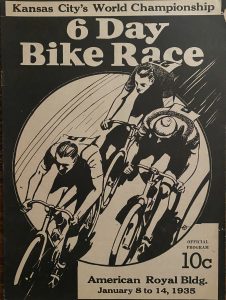

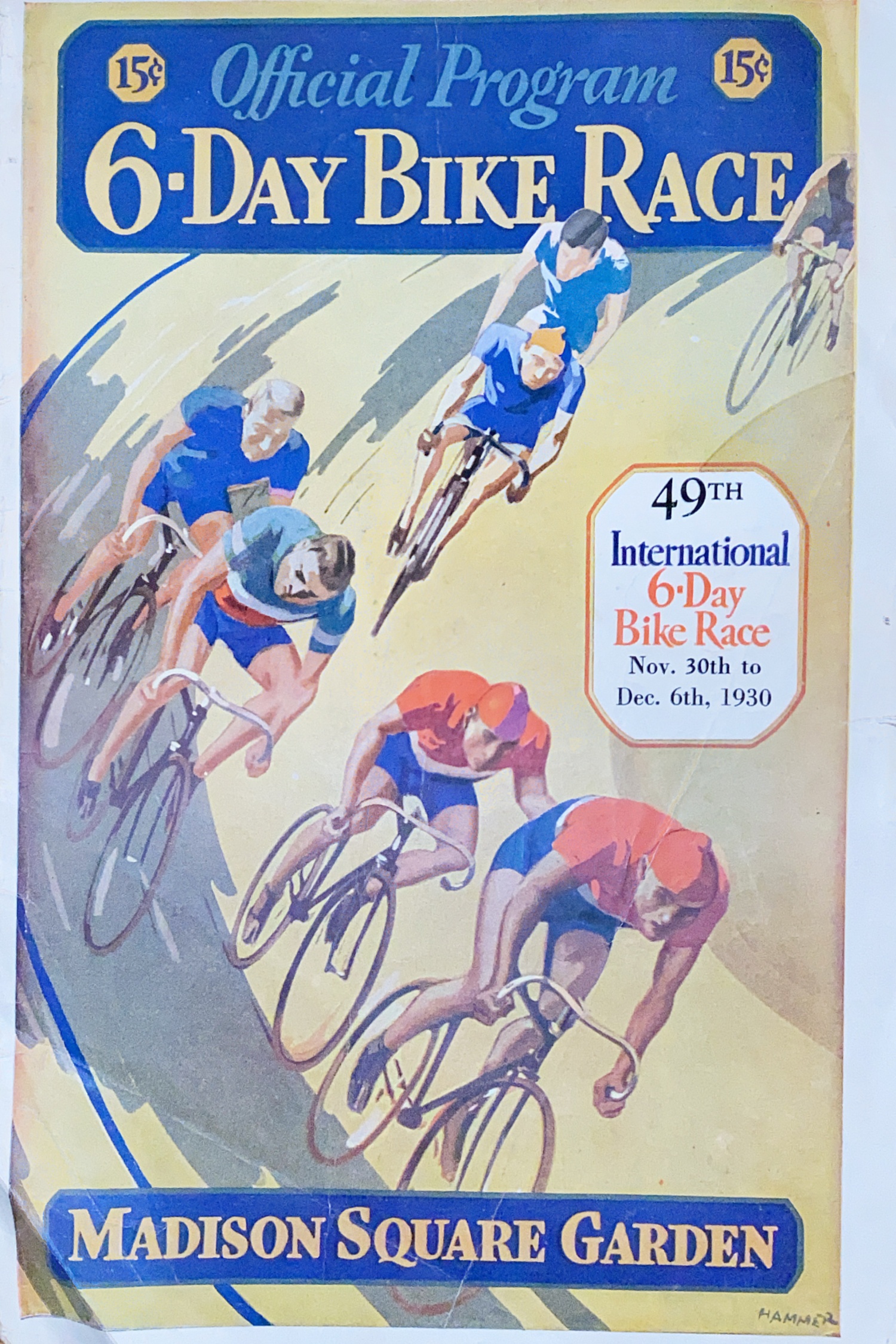

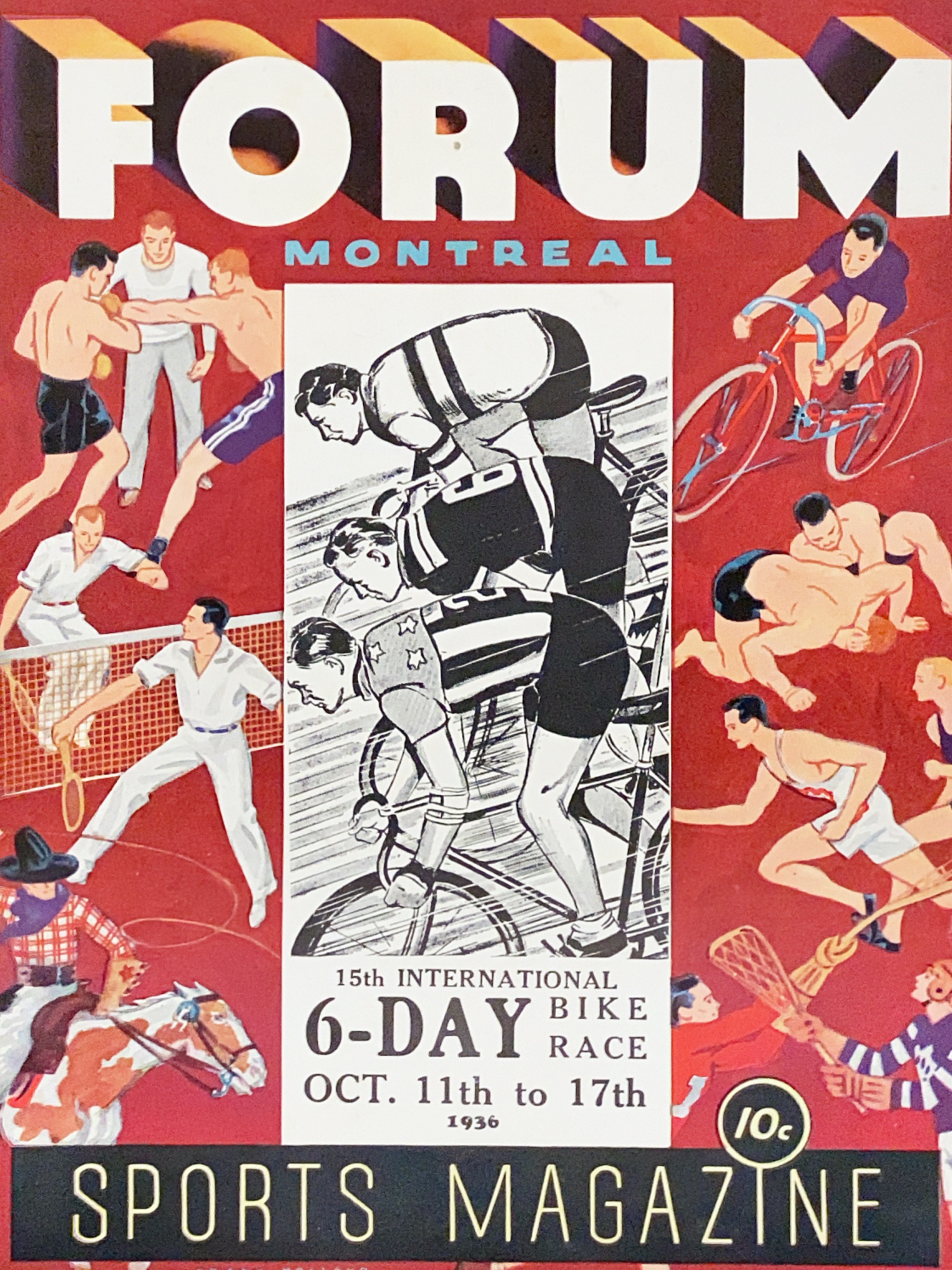

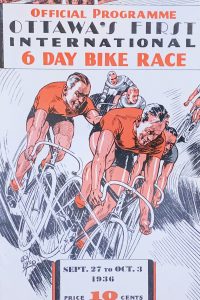

The Six Day Programs photographed are a small part of Mike Barry Sr’s Collection.

In an era when endurance events intrigued the population the bicycle races were six days long (races weren’t held on Sundays for religious reasons) and the cyclists rode for 24 hours a day. The riders never stopped pedaling as the spectators watched to witness a man reach his limit on a bicycle. Similar to endurance dance competitions where the last couple standing won, riders were expected to ride until they fell over.

Through the century the rules evolved to limit the riders’ exhaustion and to add excitement to the events. No longer do the races run nonstop for six days straight. There is now a mix of events– some mass start and others individual timed races– during the afternoons and late into the night, all designed to keep the interest of the spectators. In contrast to most of the Olympic track events, the action at a six day is relentless and the speed furious. Two man teams were also introduced as individuals had become dependent on concoctions of drugs to achieve the inhumane.

The Madison (l’Amèricaine in French) is now the main event of a modern six-day race. Named after Madison Square Gardens, where the first races took place in the 1900’s, it is a mass start event in which twelve to eighteen two man teams race each other for points sprints on given laps. One rider races while the other circles the track at the top, on its outer edge, away from the action. He rides slowly, resting and waiting to be relayed by his teammate once he tires. With a quick hand-sling the tired rider boosts his teammate up to speed as he pulls up to the rail at the outer edge of the track for a rest. Like a pit change in a car race, the exchange must be quick and efficient without impeding rival teams while or losing too much ground.

Six-day racing slowly died in the United States as cars replaced the bicycle as transport and interests changed. However, in Europe where bikes are commonly used vehicles and racing is still part of the culture, track races draw crowds of spectators, are covered by the daily media and have their champions who are professionals. In an arena, insulated from the wet and cold northern European winter, the velodrome provides a warm venue for the spectators and the cyclists.

The current series that takes place through the winter is centered in Northern Europe in the heart of the cycling world: Germany, Belgium, and the Netherlands. Cultural influences mold the ambiance in each venue where the bike race becomes and excuse to celebrate.

While the Madison is an event of tactics, agility, and fitness, the spectacle of the evening is often the motorpaced event. The crowd rises to their feet when the motorbikes roll onto the velodrome and their engines rev and spew clouds of exhaust. The cyclist tells the motorcyclist when to accelerate and when to slow down, as they work in tandem to win the event. At one time there can be half a dozen motorcycles with cyclists tight behind the rear wheel in the draft of their motorbike, racing around the velodrome.

Track racing is the purest form of cycling, as the variables are limited to the rider, the track and the competition. As a young cyclist, on the track I learned how to pedal properly. Efficiency is the essence of performance, and with time I learned to keep my upper body motionless while my legs turned in potent circles. Pedaling for hours on the Montreal Olympic velodrome I gained fitness, confidence, bike handling skills and tactical knowledge in the confined controlled environment where mistakes were often more apparent.

Although most professional road cyclists raced on the track as teenagers, few now make the transition to the six-day races in the off-season. The disciplines have both become too specific and contrasting. They lack a track rider’s skills and fail to find the quick pedaling rhythm needed to ride a fixed wheel bike smoothly and efficiently while a track rider misses the endurance, power and climbing strength of the roadman. However, a select few of the top road sprinters who grew up on the track–notably Mark Cavendish— will return to the track in the winter to smooth their pedal stroke and rediscover some speed lost in the long road racing season.

The six-day velodromes–many put together in an arena for the event and taken down immediately after–are roughly 160-250 meters around. The short lap adds to the spectacle as the riders whirl around the oval reaching speeds of 60 km/h. Unlike a road race where the spectators might only get a glimpse of the peloton as it speeds toward the finish, on the track the fans see all the action as they watch the riders for hours.

The banked corners of the oval are on average about 50 degrees. At speed the riders loop around with ease but as they slow they must keep constant pressure on the pedals, to maintain traction to ensure that they don’t slide down the banking inevitably crashing. Riding a track is a skill and racing a six-day is art.

The peloton flows with beauty around the track. The unique yet simple bikes designed for the track, without brakes and with a single fixed sprocket, combined with the smooth wooden surface, and the accomplished peloton of professionals brings fluidity. Unlike a road bike that has gears, a freewheel and brakes, a track bike is the simplest bicycle design built specifically for the velodrome where there are no corners, hills, or sudden changes in speed. The flow is only broken once the race is over, or when riders clip handlebars, or touch wheels and come crashing down.

The crashes can be horrific. Riders pile into each other and tumble, head over heals. Their bikes fly through the air, and their bodies skid across the track. Upon impact the wooden track sheds splinters. Unlike on the road where the grit from the tarmac rips the skin and dirties the wound, the wood burns and splinters pierce the skin.

The fans cheers amplify through the night with the beer, bratwurst and fries while the riders force their bodies to keep the pace until past midnight with sugary energy drinks and caffeine. Like a traveling circus moving from town to town to entertain, the six-day community is tight and insular. The riders travel with their mechanics and soigneurs (massage therapists who take care of their every need when they are off the track) from race to race, sometimes only returning home for a night or two.

Like greyhounds on a track the six-day cyclists are the show. They are bet on, cheered for, and pushed to their physical limit. Beyond the superficial gritty exterior there is art. Each with their own unique style, the track cyclists, in all their colors, manage to evoke deep emotion, inspiring the audience. Like an artist, musician or dancer, they perform their art with an apparent ease that only comes with years of practice, knowledge, experience and passion.

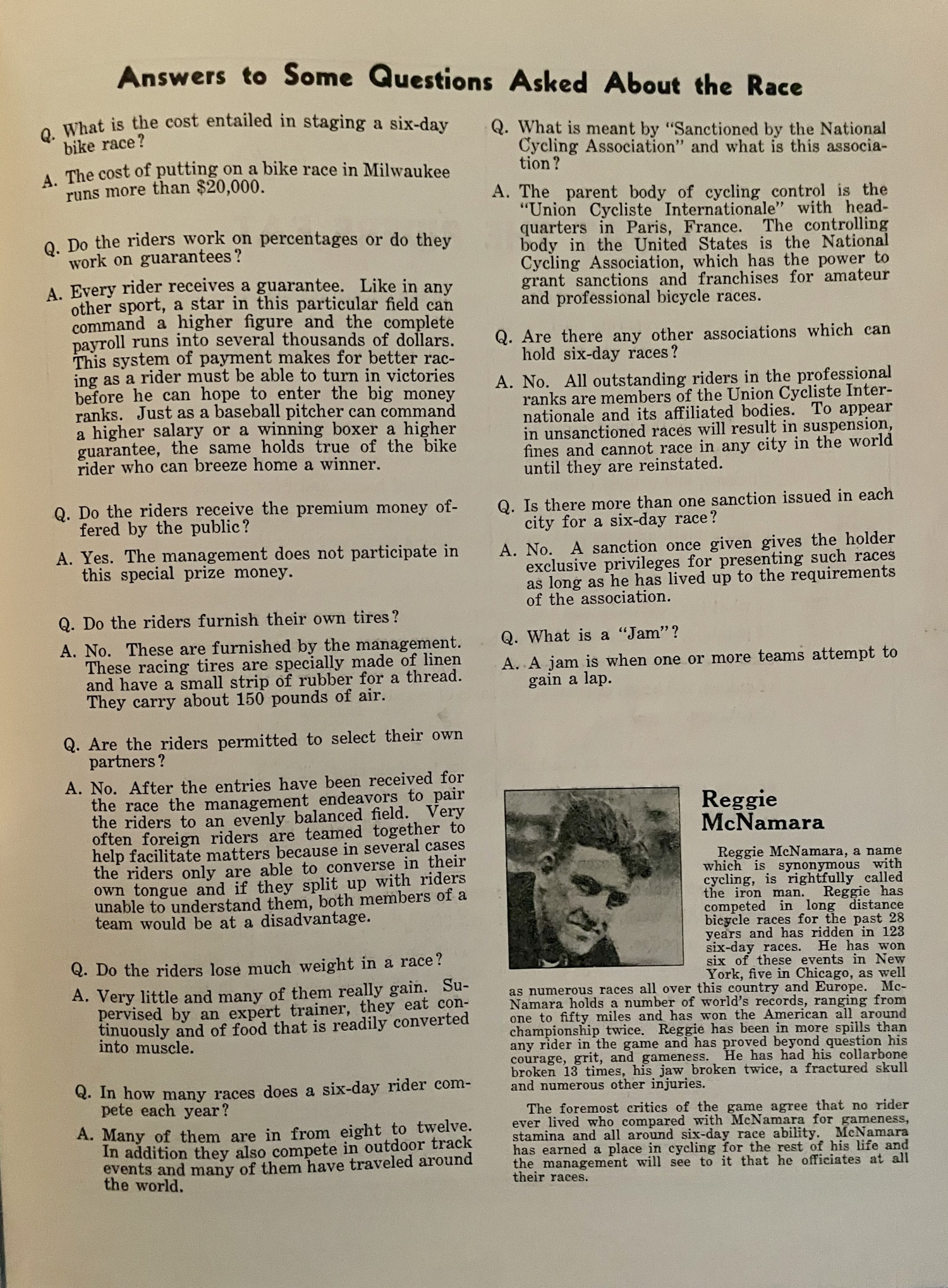

From the 1937 Milwaukee Six Day